"The Director"

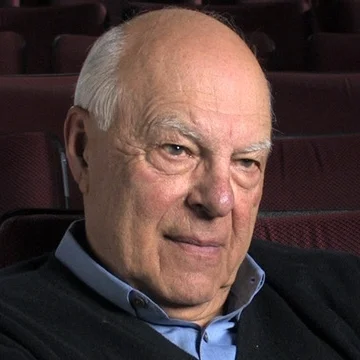

Neil Tardio is a hall of fame film director, responsible for some of the most iconic advertising ever created. His 1977 Xerox commercial, "Brother Dominic", is part of any list of the greatest Super Bowl commercials of all time. I talked to Neil about working with some of the most legendary creative figures of the last fifty years, about the challenges of marrying art and commerce in one of the most pressurized environments, the film set, and about the lasting power of creating simple human connections.

Three Takeaways

The willingness and confidence to listen to your inner voice.

Speaking the truth to power.

Creating simple human connections with your audience.

"FEARLESS CREATIVE LEADERSHIP" PODCAST - TRANSCRIPT

Episode 30: "The Director" Neil Tardio

“And I was in tears practically. The great John Barry's asking me what I think of this. I should be on my knees saying, "Oh my God, whatever. Do whatever you want." But I knew that that's not the way that you work with people like this.’

Charles:

When you hear the phrase, ‘speak truth to power’, it’s easy to think that only applies to all the people who aren’t the leader in an organization.

But the fact is that everyone works for someone. Even the leader. And being clear and resolved about the importance of speaking truth to power is even more necessary for those who already have a lot of power themselves.

When you are the leader you gain access to the levers of power. They exist inside every business. In my conversation with Adam Bryant, the creator of the corner office series at the New York Times, he said he had learned from one of his CEO interviews a simple definition of culture. This definition really resonated with me - culture comes down to two very simple things, who gets promoted, and who gets fired.

It often takes a committee to fire someone. But there is always one person who can ultimately make the decision by themselves. The leader. They might get push back, or resistance or opposition from any number of internal groups. But, when the dust settles, the leader can make the ultimate call. Who works here and who doesn’t.

Nothing shapes the future of an organization more.

When you have that kind of power, there are two ways to abuse it. Mis-using it. And not using it.

A leaders’s willingness to use power effectively depends entirely on their ability to both frame the truth and to seek the truth.

Framing the truth is the easier challenge. The best leaders have learned to frame the story through an optimistic filter. They have developed the ability to offer their people hope and a reason to try again tomorrow. The lasting success of any business depends on that skill.

But seeking the truth is much harder. It requires they flip a switch in those moments when they find themselves in the presence of whatever power they report to. Only by speaking truth to that power can they find the answer to two critical questions. What is really possible here? And what is really at stake?

Who or what has power over you? And what is the truth you need to speak to them? Answer those two questions honestly and you are a significant step closer to being a fearless leader.

Neil Tardio is a hall of fame film director, responsible for some of the most iconic advertising ever created. I talked to Neil about working with some of the most legendary creative figures of the last fifty years, about the challenges of marrying art and commerce in one of the most pressurized environments, the film set, and about the lasting power of creating simple human connections.

Charles:

Neil, welcome to the show. Thanks so much for being here. Actually, I think I should say thank you for having me here, since we're in Little Compton, Rhode Island, which is one of the most beautiful places on Earth, having just experienced an extraordinary event, the marriage of your granddaughter Maggie to the love of her life, Jesse. And I was thinking last night, as we went to this incredible wedding, everybody was here because of you and Meg. You're the people that found this place and brought everybody to it.

Neil Tardio:

That's right. Almost 50 years ago.

Charles:

50 years.

Neil Tardio:

Almost 50 years. We first ventured into Little Compton because some friends down where we live in New York were born here, and they have a summer house and invited my wife and kids to come up and spend a weekend. I visited and said, "Wow, what a spot!" So, we rented here for a while, and then bought the house in 1978. That's almost 40 years.

Charles:

Yeah, incredible. And, we're sitting in your incredible walled garden where people are actually moving around, clearing up the wedding from the night before. So, if there's some background noise, that's what's going on. But, I want to take you all the way back to your childhood. My first question which I ask almost all my guests, "What's your first memory of something being creative? Something striking you as creative, or creativity?"

Neil Tardio:

Interesting. I started drawing like most kids at an early age. And I also started drumming on my lunch box to the degree that kids used to gather around and watch me drum on my lunch box, and a teacher came over to break it up, and then heard my drumming on the lunch box, and stopped and was fascinated. And so, things like that come in. And I was really young. Maybe 5, 6 years old. But, the painting continued. My parents bought me a paint set, which I used, and eventually in those formative years, 8, 9, 10, whatever, I'd get a strong visualization of a picture I wanted to do. Never copied anything. It was always out of my head, and they would quietly tiptoe out of their bedroom, because we lived in a small, three room apartment in New York, and they'd set up a card table in the bedroom and walk out the door and say, " Look. Let the kid paint."

And I'd paint all day. And things like that were certainly drawn to me, and then I guess I started to look at pictures everywhere and then I had a friend who was painting also. He and I were big competitors in the sports world, playing ball or street football and stuff like that, and outdoor things, but he started painting too because I was painting. And, so he became a surgeon and I continued in the creative area.

Charles:

What kind of subjects were you drawn to paint? What interested you?

Neil Tardio:

One of my first paintings was a farm. I guess most kids think about the farm because teachers in school, we talk about farms, we drew one on the blackboard. And then I went home and painted a farm, and I can see it right now. And, a classic American farm. Had a barn, silo, a path leading up toward clouds, trees, a cow or two. And then I saw a calendar of the sea crashing into the rocks below a lighthouse on the New England coast. Maybe that was what drew me to Little Compton. And I painted a small little picture about 8 by 8, and we still have it and my parents loved it, said, "Wow, look at this picture." And there was a day in school and they wanted you to bring in the artwork you did at home, and I brought in this little picture and some other things and the teachers loved it.

Loved music. I used to conduct symphony orchestras. My dad was being an electrical engineer, got a wire recorder when it was the first thing out. And I played all these classical things and conduct the orchestra. And that whole process started and it was good because you certainly draw from it. And I guess I love baseball and football. I played a little football. But, I also would look at books of famous painters, Van Gogh, and Cézanne and whoever and study their pictures, and look at their brushstrokes and I'd get fascinated by the art stuff, and you certainly copy the people you like. No question about that. And why not?

So, that was the beginning.

Charles:

What did you study in college?

Neil Tardio:

Painting and drawing, and sociology was my major. And actually my dad, who was an electrical engineer who was around building all the time, the construction and stuff like that, and he thought that my penchant for art might convert to architecture and he kept telling me about, because he thought being an artist is a waste of time. You're going to wind up in Skid Row someplace. So, you want to get into a more intellectual part of it. And he thought that I should be an architect.

So when I went to college it was as an art and architecture student and so, that's how it started.

Charles:

Okay we've actually moved to one of your favorite locations in the world, your Austin-Healey. What year is this car?

Neil Tardio:

67.

Charles:

67. All right, so were sitting inside a 1967 red Austin-Healey which is in the most pristine condition and I know this is one of the great loves of your life. So back to your story. When you got out of college what did you focus on? What did you want to do?

Neil Tardio:

Well I was saying that we had a really terrific theater at school and the director of that theater Horace Robinson approached people who were in the art school art and architecture school for working on theater sets and using the talent in the school to help him get these productions on the road. And he was going to do a huge production Brigadoon and asked myself and other students to work on painting the backdrops.

So we were excited about it and he gave us a tremendous amount of information about how to do it. And we studied how other theaters had used backdrops effectively and Brigadoon has, in transitions, when you speak about in the theater sense, how to make the transitions from real life to Brigadoon, a magical Scottish place and that was done with scrims and other things like that. So I worked on that project on Brigadoon, and then he came up to me and said, "Neil, I'd like you to play a part in a production."

I said, "Oh, yeah. I haven't done any acting."

He said, "That's okay. I think you're going to be great. There's a scene in Brigadoon where Tom I think it is goes to a bar in New York, a bar that he liked a lot. And the bartender's name is Frank and he tells him about his experience in Scotland and what happened and that he is madly in love with somebody he might never see again and the whole deal." He said, "I want you to play Frank, the bartender."

So I said, "Okay."

And I liked it. And you know Brigadoon is a musical and it was really a fantastic thing. It won the National Collegiate Players Award. But more than that for me, it was a real experience in the extension and the other part of the creative world. It was really great. We had a radio TV workshop there, and I got very involved in that. We made some little films and things and one of the next show that was done, instead of working on the backdrops, we got a little crew together and put it on, on 16 mm film, and you know I guess you see something happening, and something just drives you crazy. You don't think you're doing it right. You've got to say something about it.

And that sort of itch that creative people have, and I think you could write a huge book about how to corral it, how to use it. Because it could be obstreperous. It could be insulting. You might very well be right, but the way to go about it, as my wife says to me "Why are you so angry?" I say to her.

She said, "Well it's the way you said it. It's not what you said it's the way you said it."

And I said, "Okay I'll be." so that's one of the things you have to watch out in the creative world but people get hurt. They don't want to work with you and stuff like that. So anyway, but you do have it, and it's got to come out, and it's got to be used. So I started feeling like that about things, and would tap the director on the arm and, "Mr. Robinson."

"Yes."

I said, "What about doing it like that?"

And so, he'd stop and say, "Yeah, that's not bad. Hey listen, this is what we're going to try. And so once you get successful about it, then you become a major pain in the ass.

Charles:

How did you get into film? When did that start to show up in your life?

Neil Tardio:

When I was in school in Oregon, I hitchhiked to Los Angeles, following a girl actually who lived down there whose family were in the movie business and they were going to have a big, big New Year's Eve party. She, "Oh, you can't imagine all these movie stars are going to be there."

I said, "What movie stars?"

She said, "Oh it's going to be Robert Stack and Robert Mitchum."

She went through all these names. I said "Geez."

She said, "If you can get down here, you'll be my date. We'll go."

So man, I hitchhiked to LA. Stayed at a fraternity house at UCLA and my father had a friend who worked at Disney. We always heard about him, but he was some sort of mystery man and I just called up Disney and said I wanted to see this man and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. I finally got to a secretary who said, "What do you need?"

And I said, "I want to come over there."

"Just a minute." and she said, "Can you be here at 1:00? He'd like to see you."

And I said, "Yeah. I'll find my way." Buses and whatever that got me to Disney, I walked in there. I could just couldn't believe it and out came this little man who turned out to be one of the great animator producers of the early people with Disney. And he took me in and walked me through the whole place and they were inking and painting movies, and I watched the whole process. I met the people. And the next day he said, "Listen, come back here because you said you want to get in movies or films. We're shooting this. We also produce the whole thing, so come here. Meet me and I'll take you onto the set. We're going to watch the shootings, and it'll be the best part of the whole shoot."

So I went in the studio and I watched the production, and I said, "I've got to be here. This is where I want to be. I want to be here." And so, I went back to school, but boy that was an indelible experience. So then, I started in McCann, and went through that training program and worked with this guy in production, and then an interesting thing happened. He'd bring me into a room, "Sit over here. You're going to sit in the back of this room we're going to do this creative plans, and just learn from it. Listen to what happens and the whole thing." And And I'd sit in the back of the room, watching writers and art directors present creative work. And I couldn't get over how they didn't see that something could be better or stronger or funnier. They had people. I said, "Well, that's not funny. They don't know what funny is."

And so you got build. You can't wait to get in there and do it yourself because that's another world because you're not as good as you thought you were maybe.

Charles:

When did you first get behind the camera?

Neil Tardio:

Certainly in my early days at Y & R. 25 creative people at the agency were picked by the creative director to go into a one-year process, meeting once a week with the great designer, thinker Alexey Brodovitch and Brodovitch was going to teach us how to think out of the box and so we went in this room and Brodovitch sat there picking his nose and looking at everybody and didn't say a word and somebody said, "Mr. Brodovitch, are you gonna tell us something, or what's gonna happen?"

He said, " I don't know. What do you think?"

And, "Oh, man."

So this is how it started and finally one day he had a pad and pencil, and he said, "You see this piece of paper? Make-believe this is your chance to do something in film. To do something people remember. I'm not going to write anything on here. I'm going to tear this sheet throw it on the table. You go out. I don't care whether you write, paint, draw, record, film, whatever you want. I want an expression of this. What you want to say? You got an idea? I want to hear it." He said, "We're going to meet here in two weeks, and I want to see what you do."

And that was it. So we all went out to see, "Wow, I can't believe this." I had a friend that had a 16mm film, had a little magazine on it. It was a cheap little camera, but it worked. And I got this idea about Robert Frost's poem The Road Not Taken. And I had John F. Kennedy on my mind, and so I got a piece of paper.

Charles:

Kennedy was on your mind because he'd just been killed?

Neil Tardio:

Well, a couple years before. And I found a picture of JFK, a black and white picture, and I rolled it up as if you were going to throw it away. And I put it in a little stream in the woods, and I followed it bobbing through the stream. But as it went through the stream, it opened. I knew the physics of it, that the water would open the paper and so it opens, and it opens, and opens, and little by little, you start to see who it is, and then it opens completely almost, and starts moving through the stream and interestingly, it got into a little pool and it went deeper and deeper, and I got someone to record The Road Not Taken,

"Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

and I took the one less traveled by,

And that's made all the difference."

And I shot the film, found someone who worked for Y & R, an editor, cut it. We cut it up and put it together, put the voice on it, a little production, a little mix, got it all done, brought it to the room. I got a projector, had it ready to go, and Brodovitch said, "What do you got?" And I ran it. People loved it. People were moved by it, and he shook. He saw, said, "Yeah, it's pretty good. It's okay. Good. Thanks. Next." and so that was the early stages of it.

Charles:

Were you conscious that you were developing a style at that point? An artistic point of view?

Neil Tardio:

I think so. I think so. I think the training in an agency doing creative work for somebody, let me put it this way, the thing that makes the work exceptional, maybe award-winning is that it does the job it was supposed to do, or maybe even better. In other words sell a product, a politician, a heart treatment, and anti-drug campaign, or whatever it is that people are really moved by, that people say, "Wow, this is really interesting, and that's really the power of it. That's what you get paid to do. Not so much make it beautiful, and make it memorable, does it do the job? So that's the measure of it. And that equation, it comes from particularly from advertising, is really, really a strong thing to take into other areas of the creative world whether it's music.

Later on when I start working on really big productions in the ad world, working with some of the greatest music composers there were, Maurice Jarre and John Barry, incredible, four-time Academy Award, and they, when I called them, or asked the music department, "I want to work with him."

"Oh, he's like, you can't go to him."

Then I said, "Call him."

And I would get on the phone and show them some of the work we did. They, "Sure, let's do it." They were creative. They wanted to. So, that business of making it work, making it really come off, and be exciting is what they did, and what we did, and so that was great.

Certainly during that period of time, with the golden age of that industry I was lucky to be right there and it was just fabulous because we didn't have focus groups. We had people with ideas and people who had the guts to say, "Go ahead. Do it. And here's the money to make it."

Charles:

When you were working with composing talent in that situation with that kind of reputation that kind of accomplishment, how did you get their best work out of them? What did you learn about working with them to get them to give you their best work?

Neil Tardio:

Well you, know one of the things that I think looking back on, it's a great question, Charles. When you meet them, let's take John Barry for example. I think probably the greatest James Bond. Just think of Goldfinger, and oh my God, all the things he wrote and the movies that he wrote, and Maurice Jarre, Lawrence of Arabia, and Dr. Zhivago, holy mackerel. These guys are fantastic, and the nicest most fabulous, great people.

And so I wanted John Barry to work on something, and we had to go through his agent, and I insisted that we have a conversation and John did. He said, "I want to talk to this guy before I fly back to New York." And so that first conversation with the guy like him was important to tell him what my vision was, what our vision was, the creative team, and how we saw this thing, and why we loved his work and how we could see it working with us. That was enough for him to say, "Alright, listen I'll be in New York on Wednesday. I stay at the Plaza Hotel. We'll call to let you know where. You come on up to my room and we'll talk about it."

And I did that and he said, "You know, Neil do me a favor and just come alone."

And I said, "Sure."

So I went up there and he said hello. I couldn't believe this guy was standing in front of me. And he had a piano in the room. It was a beautiful suite, and he had a piano in there. And he said, "I'm thinking about what you were talking about this, and that, and the whole thing and you were talking about this transition of winter and summer. In the winter, go to these great destinations." This was for an airline, and it was called second summer. And he said, "It's an interesting idea. I like that thing. And so getting away, some hard-working guy with family, gets his wife and goes to someplace in the sun. A little chair under a palm tree, anywhere but it's a major change in life. And it's important thing, so we want to create that transition. It's like a dream come true for them."

And I'm sitting there saying, "Boy did I get the right guy!"

And he said, "So, here. Listen to this. What you think of this?"

And I was in tears practically. The great John Barry's asking me what I think of this. I should be on my knees saying, "Oh my God, whatever. Do whatever you want." But I knew that that's not the way that you work with people like this. And he said, " Listen to this. boom boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, you know, second summer, great idea."

And I said, "I think it's good. I think it's really good."

And then we see all these winter scenes in black and white, and then they go to the sun and there's this transition, and he says, "That will be like this."

"Oh my God. When do we record it?"

So we wind up in the studio, and with a guy like John, we did the first recording ever with him in a New York studio. It was a big group there and his producer and his agent were sitting with me in the control room and they pointed to the musicians soon that walked in. They kept coming in one at a time, going over, saying hello to John and setting themselves up building this orchestra, and this guy said to me, "See this guy over there, he's probably the top. And you see this one, he's the top." And he said, "They all come because it's John. The call goes out and these are the best musicians there are in this city that do this because they want to work with John Barry. They know it's going to be a great experience."

I said, "Wow."

And then I can tell you something I know this happened with Maurice Jarre, we're working with Maurice a couple years later. His agent was a guy named Marty Erlichman. He was the agent, the toughest, smartest, brightest, most successful agent. And of course he had another Academy award when he got Maurice, was his agent. And when we first contract, "No he doesn't do commercials."

I said, "Well he might want to do this one."

"No he doesn't do them. Come on. He's working on a movie thing. Do you know who he is?"

I said, "Listen Marty, I'll fly to Los Angeles, bring him to the theater on Sunset Boulevard it's a little small theater. I'll bring my stuff and I'll run it on the screen. You don't have to say hello to me. He doesn't have to say. I just want you to be there at 11:00 next Wednesday. I'm going to be there. I'm going to rent the theater. I'm gonna bring it. I'm going to show him the stuff on the screen. If he likes it, we'll go to work. If he doesn't, leave. How's that?"

"I know that little theater. Let me talk. Okay, we'll let you know." We get a date. He said, "Okay, yeah okay. He'll be there. I'll be there. I fly to LA with the stuff, 35mm give it to the projectionist, run it, screen it, make sure it's looking good and it literally in the room comes [inaudible] sorry. I got to get this thing. In the room comes Maurice who sits down a couple rows in front of me to the right, and Erlichman next to him, and other people. Somebody waves okay to the projectionist. The lights go down and on the screen comes the stuff.

Lights come on, Maurice gets up comes over, "Hey, good to see you. I'm sorry we had to go through this drill. Come on over to my house. Let's have some lunch and we'll talk about this."

I go to his place in Bel Air and we start talking about what we're going to do. And he became a really good friend of mine I'd go out there and have dinner with them and he has this incredible wife. Just a great lovely man, but boy what a talented guy. The day we did a recording with Maurice, I heard something I didn't think was, and I touched the key in the control room and said, "Maurice, those mutes you have-" and a hand grabbed the key, and said "Hold on Maurice." and it was Marty Ehrlichman. He said, "Hey listen. You don't push the key down and talk to Maurice Jarre in a studio and tell him you got some idea you want to. You talk to me. I'm his agent. You go through me. You tell me what you think. I'll let you know whether I think it's a good idea. I don't want to bother him with that."

Maurice comes out of the studio, walks in. He sees what's going on there and said, "Neil, I'm sorry, what were you going to say?"

I said, "Well the mutes that are on the brass there in that one part, since we're talking about the exhilaration of flight, lifting off the ground, the power of flight it's all about that feeling. It means more than just flying. Isn't it? It's going you're going through a level. Whatever it is, you're making this leaving the earth, and I don't know if mutes have the timbre."

He said, "Just wait right here He walks in the studio, takes his baton, taps, "Okay, Jimmy I want you to do this drill. Fred, boom, Paul, Melissa, Marilyn." He directs the people. "Let's try. Pick it up from here. Take your take." Neil, listen to this. "Okay, ready, 1, 2, 3." Boom, he plays, ba, ba, ba, ba, ba, ba, and as it's playing, he looks at me. He goes, "Ah, this is much better." So, what a feeling that is. And then you bond with these people, and anything is possible.

Charles:

You left Y & R and you started a production company.

Neil Tardio:

Yeah.

Charles:

What was the motivation behind that?

Neil Tardio:

Just going off and doing it on my own. You have responsibilities as an advertising creative director, and I had done that and I loved going off on location in jeans and rolling in the ground looking for a shot or something, instead of wearing a suit. Not that that isn't good, but I just felt that this was a purer, more exciting way for me to do my work, so I left and the TV production business, especially the commercial production business was really reaching a real high point, and I wanted to be on that wave. I wanted to get out there and do it. And I loved the whole process. So I left and opened a little film company, and what a transition that is.

You have a big office, all the power in the world, and then you go and sit in a little rented place, waiting for the phone to ring. That's some change.

Charles:

You worked with some of the most iconic business leaders. I know you did a massive series campaign for Lee Iacocca. Your work is in the Hall of Fame. When you are working with that level, doing that kind of work, you built your reputation.

Charles:

What would you like to work for? What were you conscious that you had to bring to the set when you showed up?

Neil Tardio:

Well, you have this responsibility to do it, and to make it happen, and make it good, so I was very strong about that. Sometimes, I think I went too far, but not accepting the process can't be perfect. So although you try to make it perfect, so you can get a little intolerable about crew that don't do the right thing and stuff like that.

One thing I told a bunch of young directors once that the DGA had us do a thing is about is your chance. "Production, as you know could be a nightmare. So many things could happen, and I could go on about productions, big productions, huge things where the equipment truck broke down, or the camera wouldn't function, and you get another camera and that had something. The actress got sick, and it rained when you didn't think it would be any, and sometimes all those factors on one big shoot, and you look up at God and say, 'What did I do to piss you off?'"

But one thing I told these young directors the DGA brought there was, "Stand back and watch. The only chance you have to make a difference, if things get tough, to continue to make a difference, is to be loose enough and have the objectivity. Don't lose that view. Because they're force you to get in. That's problem. The child you're shooting is crying, doesn't want to come out of the bathroom. Whatever it is, you're going to just want to give up, but there's always a way. Try to find the way. Try to find what the key is to get it done. And you have to do that. Not just because you're being paid to do it, or because people will think you're successful. You do it for yourself. You gotta get insight. You'll have a drink tonight and you'll and say, I earned this. You really have to stand back and look at it. Don't give up."

Charles:

Were you afraid of anything during your directing career? Were there things you found you had to overcome on a personal basis?

Neil Tardio:

I think the thing I was afraid of most of all were people who you were working for who had no taste, came up with ideas that were totally wrong and would ruin something, but they were paying for it, and so you said, "How am I my going to get by this guy?" There were certain jobs you took and you went to a pre-production meeting and along came a roomful of people. As the years went on, into the 90s and late 90s, the business started to change, radically. It got harder, and harder, and harder to keep it simple, and keep it really strong with just one idea. Two people relating to each other. Everybody had their two cents and it was much, much harder.

I don't know. I think what was difficult was the process was being interrupted or not understood by somebody who was paying the bills. And who had something to say that everybody was forced to listen to, whether it was a change of wardrobe or, oh I don't know, so many things. That was what's frightening. Because they can poison the whole atmosphere. They can make you want to walk off the job and say, "I don't want to do this." And that might be at the heart of what you started this interview about fear and stuff, because in the world today, exceptionalism or creative leadership or stuff like that, there are a lot of people talking about, "There's no such thing as creativity. That anybody can learn it. Anybody can do it." And that isn't true. I'm not saying you can't approach it, but there are people as you know since the beginning of time, that paint and could write music, or do what they do better than anyone. They were incredible talented. And you should learn from that, and say, "Great." Applaud that, "I want to be like that too." and do the best you can, but don't put the person down.

I think that people like that really got in the way, and didn't like the casting. You really break your ass working on casting, which is something all directors cherish and want to do that best about, and some are good at it and some are not, but when you really know and you really work with great casting directors and the actors like what they're hearing, and the way you're building it, and somebody comes along and doesn't like anybody. They look at the casting tapes or meet the people in person, and performing in a studio, and they don't think they're right, and you look at the story board, you look at, "What are you talking about? Their part, and you say this isn't right? This is perfect."

And you want to stand up and say, "Hey, listen pal, I've been doing this for 40 years. I know. You, not. You went to business school and you're sitting here. You don't have a clue about what this is, and just because you work with this company, and you feel like you're one of the clients, you should be listening to what I'm saying. I'm trying to do the right thing for you. I'm trying to make this really good. So don't tell me that we made the wrong decision.

Consider it to a point where you understand what I'm talking about. And tell me what you think you want to do, and show me what your ideas are better. You say, 'Ah." if you make sense to me, and to these people, we'll do it. But don't just say you don't like it because it reminds you of an aunt that smacked you around when you were, I don't know." And there are people actually who are like that. They're not obstructionists. The they have no talent. They don't belong in the business. They wind up because there were looking for a job and that became more, and more, and more, the thing.

When I left the industry and retired, I met people, "Thank God. You would not stand it when you see what we have to put up with, and I do it because I have a wife and four kids and I can't wait for this to end because it's just miserable."

Charles:

Unlocking creativity in a business setting is the ultimate battle between art and commerce. And when you're a director, I think that battle is really magnified. You walk onto the set. You've got a budget. You got really specific framework and guidelines. You've got shots you got to get. How did you make the choices on a day-to-day, minute-by-minute basis about, "We've got economic reality. We've got the creative necessity." How did you juggle that?

Neil Tardio:

That's what it takes. That's where you make the big bucks, they said. That in itself is an interesting process because Elia Kazan wrote a book about what it means to be a director and it became the bible. And still is out there. And he talks about what it really means. And when you read that, he's not kidding when he says you have to be a psychiatrist, a father, a mother. You have to be a general. You have to be tough. You have to be cruel. You have to be sensitive, and he goes to all the things that director has to be. You're going to be called on to do all, or one of those things, and get it done.

So yeah, I think all I can say is that a production manager who had done, I don't know, 50, 60 movies, lots of production and whether they're good commercials or TV, or movies, it's always the same level, at the top level, same crew, same people, same whole thing, he came up to me and gave me a little nudge with his elbow and said to me, "How do you stay calm with all this going on here today?"

It was one of the shoots that was really wanted to get away. He said, "How do you stay so calm?"

I said, "You know," it's something I didn't plan on. I'm just like that. I said, "I know this. If I lose it, if I lose my patience, if I start getting crazy and angry, I'm going to block out any chance to make it better. I'm gonna block out the key. I'm not gonna see somebody in the distance beckoning me, 'Come this way.' I'm not going to see it." So you got to stay cool. You got to stay out there. It's not that I don't get upset. Because everybody looks to you. And if I collapse, "Wow."

I had a director once. He was an arrogant, successful art director who became a director and a guy that was really could be dislikable because he thought he was just the best thing that ever lived, and so he went out directing. I wished him well, and he called me up two or three months later and said, "I got to talk to you. I gotta have a little lunch with you."

I met him, and he said, "I'm having a real tough time setting up shots and the crew laugh at me, and I'm just having a tough time."

And I said, "You know Michael, you're a perfectionist. You want it to be perfect. You're looking for this perfect shot. You get there in the morning and the AD says, "Okay, where would you like the camera?" And you've already planned all this, so they set the camera up, and you don't like it, "You don't know what I mean. Move it over. Come over here." And the crew starts to go, "Oh, geez. We got one of those." So you're starting to lose the crew immediately, and the talent starts looking around, "Oh, please." They go to the bathroom. They have a cigarette. And you start losing, and it can get worse because if you see the grip looking at the other guy, saying, "Oh, Jesus, look at this creep." It's going to be hard to get them back so, he said, "That's what happened."

I said, "Here's what you do. And you, of all people, you probably rehearse it 100 times in your mind, and you storyboard, draw boards, plan, so you know you want to open up on some master shot probably. Get the camera. Say, 'I want the camera here with this thing.' Bada bing, bada boom. 'This is the shot.' Set it up. Walk away. Smoke, drink coffee, whatever you want. And if they're taking their time say, 'Come on, let's go! Let's get it done!'

They're going to say, 'Alright, alright.' and get it ready, and then somebody's say, 'Okay, sir. We're ready.' Camera's ready. Talent's standing there. Walk-up. Look at it. 'Okay. Let's go.' Boom, boom, boom. Bow. Green. Slat. 'Action.' Shoot it. Shoot it two or three times. You get this feeling, you don't think this is the right spot. Do it another take. Say, 'Okay, good I want to move.'

Move this camera over. The AD's going to say, 'You got the shot. Looked good. You sure you want to move, because we got a lot to do.'

'No, I want to come over here.' Then you're going to get shot that you really wanted that you we're too scared to find. Keep moving till you find that. You're going to find it. Shoot it, and then move on, and get it over with. Don't stand there pissing in your pants and get the crew and everybody worried about you. Make a decision. Bang, 'Let's go.' That's what directors do, we make decisions. Boom do it and then find your way. If you don't, you probably got something pretty good anyway but get on with it. Learn from that. But whatever you do, don't stall. Don't bring your nose up and drop out of the sky.'"

Charles:

I like to wrap every episode with what I described as three things. Three things that I've heard that stand out for me. So let me do that and you can tell me if they resonates for you. The first thing that strikes me is that you've always been willing to listen and have the confidence to listen to your own inner voice. You have a strong sense of what is right and what is wrong, and what is necessary to make this piece of work, whatever it was, better. And you followed that.

Second, I think, and you described this today. Your willingness to speak truth to power which I think is not all that common. But I think is always present in people who are really successful from a creative standpoint.

And the third thing, which you've also mentioned in passing, and always resonates with me, is the recognition that the best work ultimately comes down to creating really simple human connections between the maker of the work, and the person that is intended for. And without that reference point, things get bled in that are unnecessary, that become confusing, that minimize the power of the work.

Do those three resonate with you?

Neil Tardio:

Very much. Very much. Exactly. Yeah. Especially the last one, because that's really the cohesion and the language we speak as human beings. When you shoot in a foreign country or wherever you go, there's a way to start the process and then everybody joins you so, oh yeah. That's the way.

Charles:

Neil thanks so much for letting me be here today. This is an extraordinary setting. Thanks for taking the time. I've loved this conversation.

Neil Tardio:

Thank you.